Vancouver Bird Count | November 2024

Results published in the Journal of Animal Ecology

Eyster, H. N., Chan, K. M. A., Fletcher, M. E., & Beckage, B. (2024). Space-for-time substitutions exaggerate urban bird–habitat ecological relationships. Journal of Animal Ecology, 93, 1854–1867. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14194

On November 6, 2024, Harold Eyster and co-authors shared the results of the 2020 Greater Vancouver Urban Landbird Count in a peer-reviewed publication. This research project aimed to answer the question: How did bird abundance change in the Greater Vancouver area in two decades? The results are astonishing.

Photo: Harold Eyster, research lead.

Greater Vancouver lost a quarter of its birds in 20 years

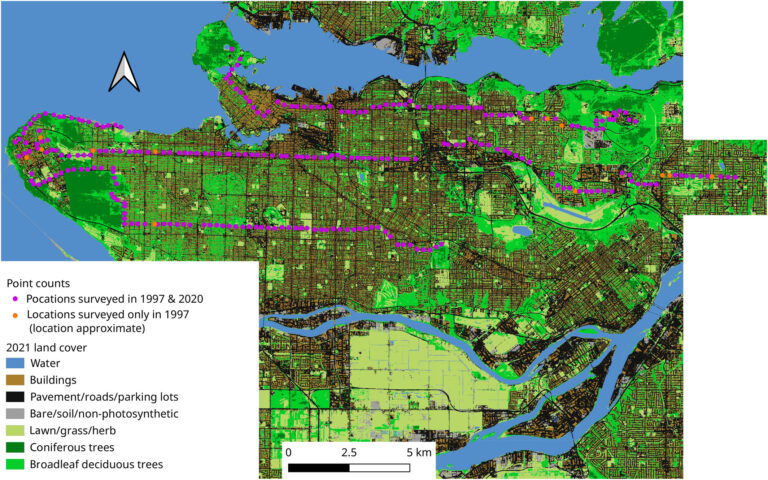

In the summer of 2020, the research team conducted repeated bird surveys at 272 Greater Vancouver locations (purple points on the map below) to count breeding landbirds. The locations were selected based on the historic bird survey by Dr. Stephanie Melles in 1997. This study design allowed for a direct comparison of bird statistics collected 23 years apart.

“Map of Greater Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada showing 2021 land cover (different colours) and locations of 1997 and 2020 bird surveys (circles; purple circles are replicated surveys, yellow circles are those only surveyed in 1997)”. Source: Eyster et al., 2024.

Research findings revealed that the overall abundance of breeding birds in Greater Vancouver decreased by 26% from 1997 to 2020.

Eyster et al., 2024

In addition to overall losses in bird abundance, the compositions of the bird community and common bird species also changed in 23 years. Some species have increased in numbers (like Anna’s Hummingbird, White-crowned Sparrow, Northern Flickers, Black-capped Chickadees, Pine Siskins and American Goldfinches), while others experienced a significant drop in numbers (for example, House Finches, Violet-green and Barn Swallows (a species of special concern in Canada), American Robins, Spotted Towhees, American Crows, European Starlings, and House Sparrows). Of note, the top five most common species in 1997 included the ones that showed a drastic decline in 2020 (European starlings, House Sparrows, American crows, House Finches, and Violet-green Swallows).

This trend is not new. Since the 1970s, nearly 3 billion birds have been lost in North America. The 2024 State of Birds in Canada report showed that Canada has lost nearly 40% of all birds, with grassland birds alone experiencing the most drastic decline of 67%.

What is causing the bird decline?

While it was not the focus of the study to determine the causes of the decline in bird abundance, the authors shared several hypotheses as to what may be causing it. Possible impacts included “interspecific interactions, regional species pool effects, changes in arthropod abundance, climate change, microhabitat specificity, and changes in anthropogenic food subsidies.” When it comes to human-caused sources of bird mortality, studies show that the top two are domestic cats and window collisions, both of which cause millions of bird deaths in Canada each year (Blancher et al., 2013; Calvert et al., 2013).

Why is it important to study urban birds?

Birds are important indicators of ecosystem health, and they provide valuable ecosystem services that benefit both the environment and people. However, they are studied more often in their natural, rural habitats than in urban areas. Eyster et al. (2024) emphasize that not all bird species can adapt to urban living. Moreover, the authors point out that urban birds face distinct pressures, including exposure to pollutants, collisions with glass buildings, encounters with urban predators, and diseases associated with high-density feeders. Research focused on urban environments is crucial for understanding variations in bird activity and adaptation across different landscapes.

The authors also highlight the benefits of urban birds for humans, such as improved well-being, positive experiences from interactions with birds and nature, and equitable access to green spaces. Additionally, cities provide opportunities for people to create habitats for birds and supplement their diets through bird feeding. Thus, understanding bird dynamics in urban settings can help inform conservation practices tailored specifically for these environments and ensure we can support urban bird populations valuable to our communities.

Visit our Cats and Birds Research page to learn more about this research project and find out how to keep pets and wildlife safe on our Cats and Birds pages.