Cats and Birds | Human Health

Cats are the most popular pet in North America, with over 9 million cats estimated to live in Canadian homes (CFHS, 2017). They are loved companions who can bond with humans and provide emotional support. However, a cat’s lifestyle can pose potential risks to human health and the health of our ecosystems.

Cats, like other animals, can give certain diseases to humans, called zoonotic diseases. In some cases, the risk of zoonotic disease transfer between humans and cats (as well as between cats and other animals) is higher when cats are allowed to go outdoors freely and hunt wildlife. They can also become infected through their surrounding environment.

While any healthy person may experience symptoms of zoonotic diseases, people who are immunocompromised or pregnant can be at a higher risk of serious symptoms if exposed. Talk to your doctor or veterinarian for information and advice on the treatment and risks associated with these diseases.

Cats and Zoonotic Diseases

The Stewardship Centre for BC supports the One Health perspective, which recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and the environment are interconnected. For example, the health of companion animals like cats is linked to the health of human communities, as the two exist in close proximity. Therefore, solutions to issues like diseases transferred from cats to humans and other animals should consider the benefits to humans, animals, and their environment.

This article will briefly review three prominent zoonotic diseases (Toxoplasmosis, Cat Scratch Disease and Salmonella) that can be passed from cats to humans, in addition to other pets and wildlife, and outlines key steps you can take to decrease their spread.

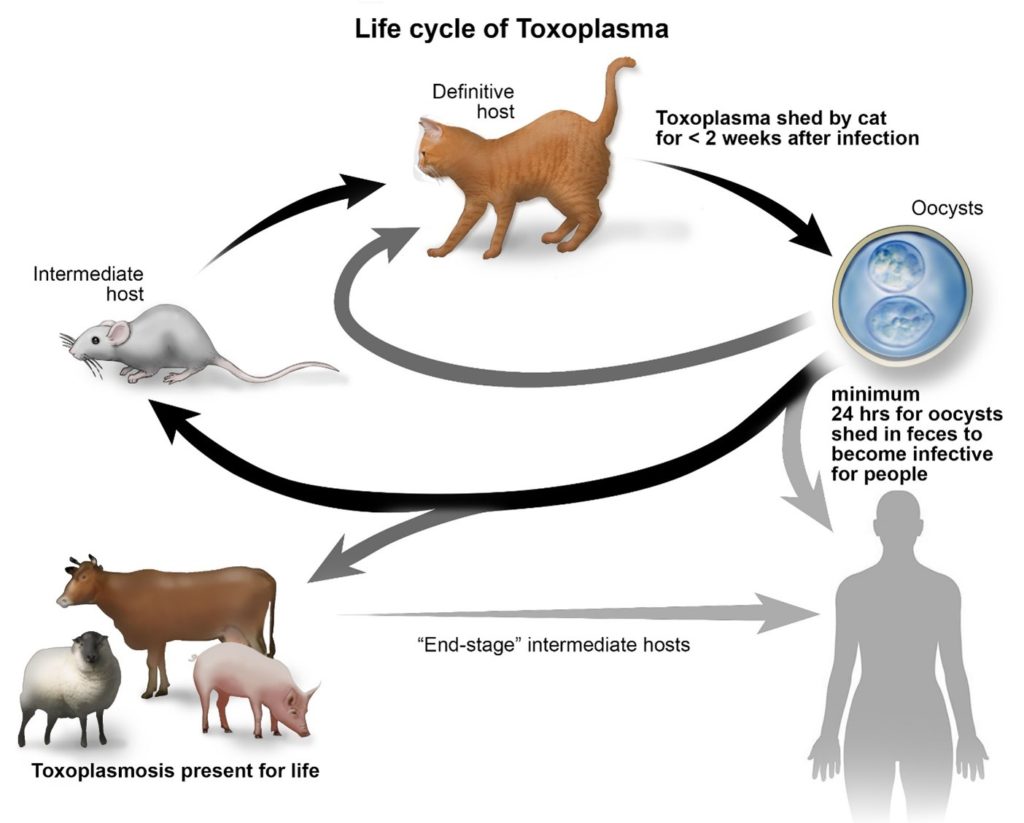

The life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii (Cornell Feline Health Center, 2018).

Sometimes called “Kitty Litter Disease,” toxoplasmosis is caused by a widespread microscopic parasite called Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii). All warm-blooded animals, including people, cats, birds, and other wildlife, can become infected (CDC, 2020a).

All species of cats, both domestic and wild, play an essential role in the life cycle of Toxoplasma because they are the only animal that can shed the parasite’s eggs into the environment, which go on to infect other animals and humans. The eggs are shed through a cat’s feces, which can remain in the soil and water for years (Wilson et al., 2021).

Cats and other non-human animals may commonly become infected with Toxoplasma through ingesting the eggs in the environment, by hunting and eating infected prey like birds, rodents, and other wildlife, or by transmission from an infected mother to her fetus (Elmore et al., 2010).

Similarly, humans can become infected by ingesting eggs from infected cat feces, usually from improper hand washing after cleaning the litter box or contact with soil or water in places where outdoor cats poop, like gardens or sandboxes (Elmore et al., 2010). Like in cats, human infection can be passed from mother to child or from eating undercooked infected meat (Elmore et al., 2010).

The risk of infection for cats can depend on how much time they spend outdoors unsupervised and whether they’re hunting wildlife. For example, a 2004 study found that indoor-only pet cats had the lowest instances of T. gondii infection followed by pet cats with outdoor access, while feral outdoor-roaming cats had the highest infection rates (Nutter et al., 2004).

Risks to Human Communities

Infection with T. gondii can cause health concerns for healthy people, including flu-like symptoms or eye infections in some cases (Dubey, 2021; CDC, 2018). It is also important to note that because the parasite remains inactive in a person’s body after the initial infection, toxoplasmosis symptoms may appear over time if an individual later becomes immunocompromised (CDC, 2018).

While cats can shed infectious eggs, simply owning a cat does not necessarily put you at risk of becoming infected, especially if proper precautions are taken (Elmore et al., 2010). Talk to your doctor or veterinarian if you are concerned with your personal risk of infection.

Risks to Ecosystems

Toxoplasmosis also negatively affects wildlife populations. A 2021 UBC study found that wildlife is more likely to be infected with toxoplasmosis where human density is higher, and rates of infection in wild animals are increasing alongside human population growth (Wilson et al., 2021). This is likely because cat populations also tend to be higher where humans live: about one in three Canadian households has a pet cat (CFHS, 2017). As it’s likely that both unowned and owned domestic cats are contributing to this parasite’s spread in the environment, cat owners can play a role in its transmission.

Prevention

- Keep your cats strictly indoors or only allow them supervised outdoor access to reduce their risk of becoming infected and reduce the shed of the parasite into the environment.

- Pick up after your cat if they defecate outside while supervised or on a leash.

- Clean the litter box daily, as it takes a least 24 hours for the eggs to become infectious (CDC, 2020a).

- Dispose of cat litter in a plastic bag and put it in the garbage only.

- Practice proper hand hygiene after cleaning litter or coming into contact with soil.

- Thoroughly wash fruits and vegetables from the garden to avoid ingesting infected soil.

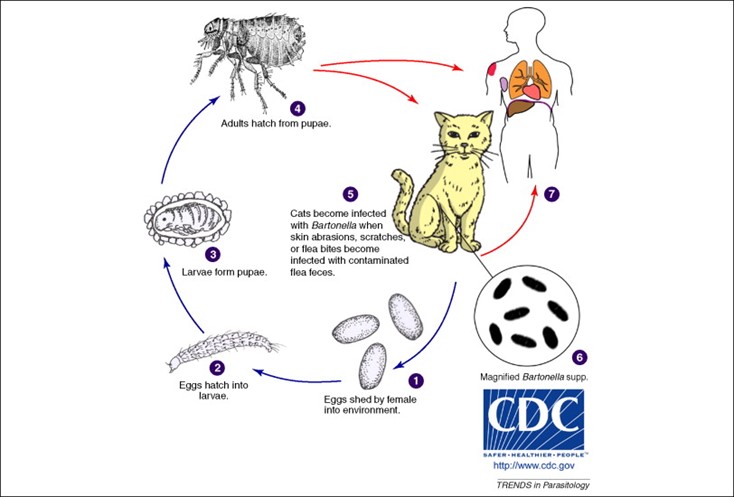

Common transmission cycles of cat-scratch disease (McElroy et al., 2010).

Cat scratch disease (sometimes known as cat scratch fever) is a bacterial infection that can be passed from infected cats to humans through scratches or bite wounds. Symptoms are flu-like, but can sometimes appear more serious, especially in children or immunocompromised individuals (CDC, 2020b).

Cats become infected by a bacteria called Bartonella henselae, carried by a common species of flea called the Cat flea. Kittens under one year old are especially at risk of having and transmitting it, as they’re learning to play and hunt and are more likely to scratch and bite (Nutter et al., 2004, CDC, 2020b).

Prevention

- Keep pet cats indoors and only allow supervised access to most effectively reduce the risk of infection and transmission.

- Regularly treat your cat with a veterinarian-approved anti-flea medication if they frequently go outdoors (supervised or not).

- Play gently with cats to avoid scratches and bites.

- Do not encourage licking behaviour, and do not let a cat lick someone’s open wound or scab.

- Wash hands thoroughly after a scratch or bite.

Salmonella is caused by a bacterial infection. You probably know it as a food-borne illness, but it can also be transmitted from cats to humans and other animals. It’s spread through contaminated soil or water or contact with infected feces, either through direct contact when cleaning the litter box or while gardening or playing in the soil where a cat has defecated (CDC, 2022).

Cats can become infected by preying on infected birds, rodents, and other wildlife, as well as by eating raw or undercooked meat or by coming into contact with contaminated water or soil (Rosario et al., 2022). Outdoor roaming cats, especially feral cats who frequently hunt wildlife, have a higher potential to transmit salmonella to other pets, wildlife, and humans, posing a concern for public health (Rosario et al., 2022). Cats may also find it easier to prey on birds and small mammals who are sick with the infection and go on to become infected themselves.

Prevention

- Keep cats indoors and only allow supervised outdoor access to decrease your cat’s risk of becoming infected by hunting wildlife or drinking contaminated water.

- Pick up after your cat if they defecate outside while supervised or on a leash and dispose of droppings in the garbage.

- Avoid feeding your cat raw or undercooked meat, and consult your veterinarian if you wish to do so.

- Practice proper hand hygiene after cleaning the litter box or coming into contact with infected soil.

Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS). (2017) Cats in Canada 2017: A Five-Year Review of Cat Overpopulation. https://humanecanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Cats_In_Canada_ENGLISH.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Toxoplasmosis – Disease. Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection). Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/disease.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020b). Cat scratch disease. Healthy Pets, Healthy People. Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/cat-scratch.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Cats – Diseases. Healthy Pets, Healthy People. Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/cats.html

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020a). Toxoplasmosis – biology. Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection). Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/biology.html

Dubey, J. P. (2021). Outbreaks of clinical toxoplasmosis in humans: Five decades of personal experience, perspectives and lessons learned. Parasites & Vectors, 14(1), 263-263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04769-4

Elmore, S. A., Jones, J. L., Conrad, P. A., Patton, S., Lindsay, D. S., & Dubey, J. P. (2010). Toxoplasma gondii : Epidemiology, feline clinical aspects, and prevention. Trends in Parasitology, 26(4), 190-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.009

Nutter, F. B., Dubey, J. P., Levine, J. F., Breitschwerdt, E. B., Ford, R. B., & Stoskopf, M. K. (2004). Seroprevalences of antibodies against bartonella henselae and toxoplasma gondii and fecal shedding of cryptosporidium spp, giardia spp, and toxocara cati in feral and pet domestic cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 225(9), 1394-1398. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15552314/

Rosario, I., Calcines, M. I., Rodríguez-Ponce, E., Déniz, S., Real, F., Vega, S., Marin, C., Padilla, D., Martín, J. L., & Acosta-Hernández, B. (2022). Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotypes isolated for the first time in feral cats: The impact on public health. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 84, 101792-101792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2022.101792

Stella, J. L., & Croney, C. C. (2016). Environmental aspects of domestic cat care and management: Implications for cat welfare. The Scientific World, 2016, 6296315-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6296315

Wilson, A. G., Wilson, S., Alavi, N., & Lapen, D. R. (2021). Human density is associated with the increased prevalence of a generalist zoonotic parasite in mammalian wildlife. Proceedings of the Royal Society. B, Biological Sciences, 288(1961), 20211724. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1724

Key tips for protecting cats and humans from zoonotic diseases

Keeping cats indoors is the best way to decrease their risk of exposure to these diseases. Only allowing your cat supervised outdoor access will also limit the addition of the mentioned parasites or bacteria into the environment and will protect other pets, wildlife, and humans.

Supervising your pet cat on a leash or in an outdoor enclosure like a catio is an effective way to allow them to enjoy the outdoors while restricting their ability to prey on wildlife and come into close contact with cats and other pets or wildlife.

Even if kept indoors, scheduling routine veterinary checkups for your cat is always a vital component in keeping your pet healthy and happy.

Reduce the risk of zoonotic diseases by keeping your cats at home and supervising them when outdoors through leash-walking or catios.

Visit our website to learn more about the Cats and Birds project and how to make your community safer for cats, birds, other wildlife and people.