About Garry Oak Ecosystems

Why are they important?

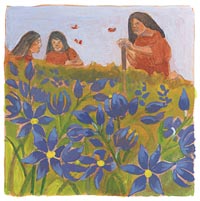

Painting by Briony Penn, courtesy of City of Nanaimo

Prior to European settlement, much of southeastern Vancouver Island was dominated by Garry oak ecosystems, playing an important role in the rich and complex culture of the First Nations of this region. In the past, some First Nations deliberately burned selected woodlands and meadows to maintain open conditions and promote the growth of berries, nuts and root vegetables such as camas.

To early settlers, the openness of the rolling landscape offered a bright contrast against the conifer-dominated woods. In the year of Victoria’s founding as “Fort Camosun” by the Hudson’s Bay Company, Chief Factor James Douglas described the natural setting as “a perfect ‘Eden’ in the midst of the dreary wilderness of the North”.1 Over time, much of the meadows and woodlands were converted to farmland and pasture, displacing the native flora and fauna.

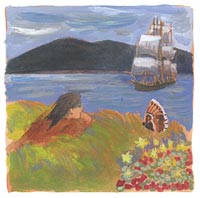

Painting by Briony Penn,

courtesy of City of Nanaimo

Although much of the Garry oak habitat has been altered since Douglas wrote his words, many of the stately oaks still stand as a testament to the vast expanse once occupied by their associated natural systems. As well, the more-intact patches that have escaped development pressures still bring an aesthetic admired by many who encounter them. Protected areas such as Mount Tolmie in Saanich, Mount Tzuhalem near Duncan and Ruckle Park on Salt Spring Island provide delightful viewscapes and places of serenity to walk and enjoy nature.

Conservation efforts are often motivated by a recognition that humans have played a major role in altering these landscapes and that we must alleviate the devastating effects of our actions. For many, protecting these ecosystems represent a respect for the environment and a humble acknowledgement of humankind’s relationship with the natural world. If we wish for future generations to be able to experience the richness and beauty of these natural areas, we must make an effort to maintain, and expand on, what is left of Garry oak ecosystems to the best of our ability.

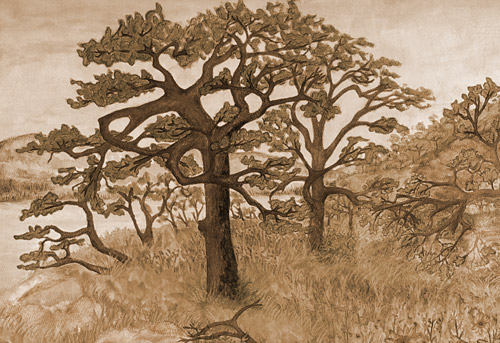

Artist’s rendition of a Garry oak ecosystem prior to European settlement (by David McPhie)

Garry oak and associated ecosystems combined are home to more plant species than any other terrestrial ecosystem in coastal British Columbia. Many of these species occur nowhere else in Canada. These habitats also support 104 species of birds, 7 amphibians, 7 reptiles and 33 mammal species; eight hundred insect and mite species are directly associated with Garry oak trees.

The ecosystems arose during a warm interval 7,000 to 10,000 years ago and covered a much greater area than they do today. Due to invasions of exotic species and land development for agricultural, industrial and urban use, habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation are occurring at a rapid, accelerating rate. As a result, less than 5% of the original habitat remains in a near-natural condition and more than 100 Garry oak and associated ecosystem species are at risk of extinction. In the context of conservation, saving what is left has become critically important.

In the future, Garry oak and associated ecosystems may play an increasingly important role in Canada with the progression of global climate change. Species in these ecosystems are adapted to a warm climate with an extended summer drought. We need comprehensive conservation strategies to ensure that all of the resident species survive and spread into new sites if they become available. Garry oak ecosystems may well be part of the landscape of the future.

Why do they need protection?

Unfortunately, people often focus only on the oak trees, not the ecosystems, when considering protection measures and conservation strategies such as tree protection and replanting bylaws, and development zoning.

This leads to well-intentioned politicians, planners, developers and landowners who feel that they are protecting Garry oak ecosystems when they spare a few trees. This often results in small islands of native trees surrounded by a sea of exotic plants or pavement.

However, it is never too late to take action; this shift in this trend is occurring. Development can proceed with the protection of Garry oak ecosystems in mind. Gardeners and restorationists can establish or restore Garry oak habitat in their community.

References

- James Douglas to James Hargrave, February 5, 1843, G.P. de T. Glazebrook, ed. The Hargrave Correspondence, p. 420